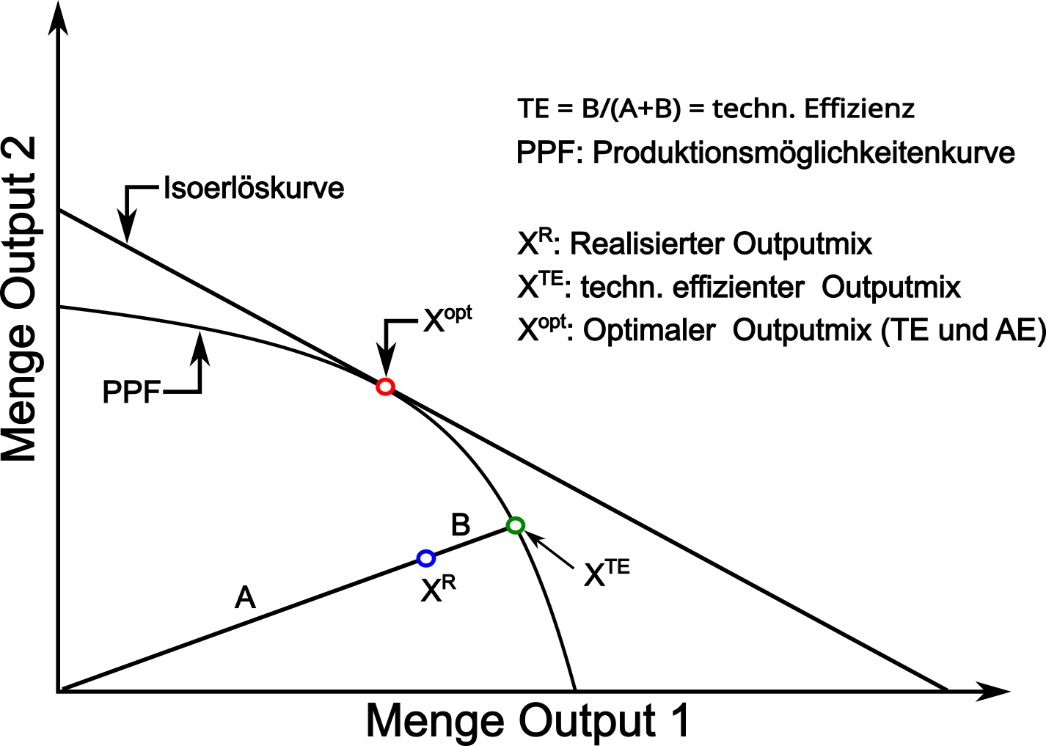

In economic theory, the assumption of the optimising behaviour of actors (e.g. maximising profit, revenue, the quantity produced) forms the basis of business management. For example, companies try to maximise profit (in the long term) with given resources. The ability of a company to generate the maximum possible profit/revenue is referred to as efficiency (Kumbhakar and Lovell 2003). Efficiency can be divided into several components: technical efficiency (TE) and allocative efficiency (AE) are the most frequently analysed (Figure 1). Technical efficiency describes the difference between a realised production quantity and the maximum quantity that can be produced, given the inputs. For example, company A is technically more efficient than company B if company A manages to produce more output than company B with the same resources or inputs or if it manages to produce the same output as company B with fewer inputs. Allocative efficiency in output describes the optimality of the product mix as a function of producer prices. A producer's output mix is allocatively efficient if output X cannot be exchanged for output Y without reducing revenue or profit. Allocative efficiency means that in a society, products are produced according to their respective benefits (represented by the price) and thus scarce resources are optimally utilised.

Figure 1: Production possibilities and efficiency of a farm with two outputs

The efficiency of farms can be measured using stochastic (econometric - stochastic frontier analysis) and deterministic methods (Coelli et al. 2005). The deterministic methods include data envelopment analysis (DEA), which is particularly suitable for dividing the efficiency of a farm into technical and allocative efficiency (Pascoe et al. 2022). In addition to the classic DEA, there are now numerous variants with which stochastic elements (e.g. via bootstrapping) can also be incorporated into the deterministic efficiency analysis (Bogetoft and Otto 2010) in order to better reflect the uncertainty of the results. While technical efficiency in the agricultural sector (e.g. Brümmer and Loy 2000; Djokoto 2015; Latruffe et al. 2017; Nowak, Kijek, and Domańska 2015; Thiam, Bravo-Ureta, and Rivas 2001) and fisheries (Dresdner, Campos, and Chávez 2010; Estrada, Suazo, and Dresdner Cid 2017; Koemle et al. 2023; Pascoe 2007) has already been analysed many times, there is still a great need for research on allocative efficiency.

The determinants of the various components of efficiency (TE and AE) can be estimated using analyses downstream of DEA. For policy measures that are not randomly distributed in the population, e.g. because they are implemented on a voluntary basis, the measurement of policy effects requires the application of causal analysis methods (Cunningham 2021; Pearl, Glymour, and Jewell 2016). A practical example of these measures is the Austrian agri-environmental programme ÖPUL, in which measures for environmental, nature and water protection are promoted with the voluntary participation of farmers. In fisheries, fishing capacities are reduced through subsidised temporary or permanent decommissioning of fishing vessels (Koemle et al. 2023; Lado 2016), while capacities are also increased through investment subsidies to increase the competitiveness of the fishing fleet (Lado 2016). Figure 2 shows examples of the causal relationships between policy adoption by individual participants and efficiency, depending on measurable characteristics of the company (X), external factors (Z, e.g. regulations, policy measures, environmental effects) and unmeasured factors (B), which lie, for example, in the personality, ability and psyche of the acting person. Due to the influence of unmeasured effects on policy adoption and efficiency, the causal effect of policy adoption on efficiency can be analysed.

The determinants of the various components of efficiency (TE and AE) can be estimated using analyses downstream of DEA. For policy measures that are not randomly distributed in the population, e.g. because they are implemented on a voluntary basis, the measurement of policy effects requires the application of causal analysis methods (Cunningham 2021; Pearl, Glymour, and Jewell 2016). A practical example of these measures is the Austrian agri-environmental programme ÖPUL, in which measures for environmental, nature and water protection are promoted with the voluntary participation of farmers. In fisheries, fishing capacities are reduced through subsidised temporary or permanent decommissioning of fishing vessels (Koemle et al. 2023; Lado 2016), while capacities are also increased through investment subsidies to increase the competitiveness of the fishing fleet (Lado 2016).

Figure 2 shows an example of the causal relationships between policy adoption by individual participants and efficiency, depending on measurable characteristics of the organisation (X), external factors (Z, e.g. regulations, policy measures, environmental effects) and unmeasured factors (B), which lie, for example, in the personality, ability and psyche of the acting person. Due to the influence of unmeasured effects on policy adoption and efficiency, the causal effect of policy adoption on efficiency cannot be identified without further assumptions.Frequently used identification strategies are, for example, difference-in-differences (DiD), propensity score (matching), instrumental variables or other counterfactual methods.Machine learning methods are also used as part of the further development of the aforementioned classic methods (Bach et al. 2024; Chernozhukov et al. 2018; Huber 2023).

Figure 2: Directed acyclic graph of the causal drivers of efficiency. The relationships shown in orange are unobserved; the identifiable effect is that of policy adoption (blue)

A combination of DEA and machine learning methods offers new and exciting possibilities for evaluating policy measures. Compared to traditional regression-based methods for causal analysis, the application of machine learning offers several advantages: (1) machine learning models can adapt better to the data and therefore make better predictions than classical statistical models; and (2) machine learning models make fewer restrictive assumptions (e.g. on the functional form of the relationships between variables), but learn the structure of the (non-linear) relationships from the data. With the double machine learning method, high-dimensional explanatory variable sets (= data sets with many variables) and non-linear relationships can therefore be taken into account and causal policy effects estimated. Depending on the question, different methods are available (e.g. partial linear regression, interactive regression model, DoubleML-based DiD, etc.; Bach et al. 2024). A distinction can be made between homogeneous and heterogeneous policy effects (i.e. policy effects that work differently depending on the characteristics of the participating company). The R package DoubleML (Bach et al. 2024) also allows causal effects of several influencing variables to be determined simultaneously based on bootstrapping.

In this project, a data set from commercial fisheries in the German Baltic Sea serves as a case study for measuring the influence of policy measures on allocative efficiency. Like many global fish stocks (Pauly et al. 2002; Pikitch 2012), the stocks of the so-called breadfish species cod (Gadus morhua) and herring (Clupea harengus) in the Baltic Sea have collapsed massively (Möllmann et al. 2021), resulting in a large number of regulations and reductions in the respective catch quotas. In addition, the coastal region of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in particular, including its fisheries, has undergone major structural change since the fall of communism in 1989 (Lewin et al. 2023; Kotte and Stöckmann 2024). For policymakers, this results in a conflict of objectives between food security, maintaining an efficient fishing fleet and the associated jobs, and the long-term conservation of resources (the availability of catchable fish stocks).Fisheries are subject to a complex, multi-layered regulatory framework: the European Common Fisheries Policy works to conserve fish stocks (e.g. through quotas for cod and herring; fleet policy), as do national regulations and rules at federal state level for coastal areas (e.g. Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania's coastal fishing regulations).Regulation includes input- and output-orientated measures. Input-oriented measures limit or reduce the fishing effort and/or the effectiveness with which fishing is carried out, e.g. temporary closures, scrapping premiums, technical restrictions (maximum power, minimum mesh sizes, prohibition of certain fishing methods, area-specific restrictions on net lengths and hooks), closed areas or closed seasons. Output-orientated measures, on the other hand, limit the amount of fish that can be taken, e.g. through (individual, tradable) quotas. In addition to fisheries management, external factors such as weather or markets also influence fishing decisions and the realised catches and profits.

Most waters in the Baltic Sea region contain several fishable species (e.g. herring or cod in the Baltic Sea, freshwater species such as pike, perch or zander in brackish water areas such as the Rügen Bodden). By knowing the fish behaviour at different times of the year, the local habitats and the suitable fishing gear, fishermen can fish for specific species (including fish sizes) in a more or less targeted manner (Pascoe, Koundouri, and Bjørndal 2007; Koemle et al. 2024). The choice of target species on the farm is driven by the fishing gear (fishing vessels, traps, gillnets or trawls, etc.) as well as the availability of catchable fish and its value (price), but is also influenced by various policy measures (e.g. quotas or other landing rights). Depending on the fishing operation, however, the flexibility to react to current market developments is limited, as new equipment must be purchased (and approved) or new knowledge (how/where can the target species best be caught, what competitors do I have at sea, etc.) must be built up in order to change a target species, for example. This results in sources of technical or allocative inefficiency that should be analysed in the proposed project.

Objectives

Main objectives

- To estimate the causal effect of different policy measures on the output-allocative efficiency of firms.

- International networking and development of methodological expertise

Detailed objectives

- Detailed description of the literature on the effect of policy measures on efficiency in the context of food production with a focus on fish.

- Description of fisheries in the case study area.

- Calculation of allocative efficiency using data envelopment analysis (non-parametric efficiency analysis).

- Use of Causal Machine Learning to separate causal effects of policy measures on efficiency from pure correlations.

- Derivation of conclusions and recommendations

Work packages

This project aims to estimate the determinants of the allocative efficiency of fishing enterprises using deterministic efficiency analysis and causal machine learning. The project consists of four interrelated work packages (WP 1-4) and a control package (WP 0).

Work package 0: Project management

At least three project meetings with all project partners are planned:

A kick-off meeting via Zoom with all international project partners will be organised at the beginning of 2025. A general exchange on the state of knowledge will take place, the research questions will be concretised and decisions on the efficient exchange of knowledge, data and literature will be made. Possible hurdles will also be discussed and solutions proposed.

A second project meeting via Zoom will be organised in the second half of 2025 to discuss the current status of the project. Here, necessary decisions will be made, the progress of the project in its various areas of work will be presented and final agreements will be reached on the analysis and development of the core statements (methodologically and in terms of content).

At a third project meeting in mid-2026, a draft for the final report will be discussed, final decisions will be made for a scientific publication and the intended journal will be determined. The corresponding final documents (report and scientific article) will then be finalised

Work package 1: Literature analysis and method review

Dieter Kömle, Yifan Lu, Christoph Tribl, Robert Arlinghaus

In work package 1, three strands of literature are analysed: First, it is investigated which forms of non-parametric efficiency analysis are particularly suitable in the given context to calculate allocative efficiency in output (Asche and Roll 2018; Koemle et al. 2023; Pascoe et al. 2022; 2003). In addition, the literature on causal inference methods in conjunction with machine learning is analysed. Third, the literature on fisheries policy in general (analyses of the development of fisheries policy, different support programmes and regulations; (Lado 2016; Sumaila 2013; Sumaila, Bellmann, and Tipping 2016)) and specifically in Baltic Sea fisheries will be surveyed (Arlinghaus et al. 2023; Möllmann et al. 2021). Preliminary work by the Thünen Institute and the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries is used to break down the fisheries policy measures in the Baltic Sea. Based on this first step, the concrete procedure for estimating the causal effects and the specific policy measures to be analysed are defined.

Work package 2: Data acquisition

Dieter Kömle, Gabriele Scheufele, Yifan Lu

Work package 2 comprises the acquisition of the necessary data. Data on commercial fisheries will be acquired through co-operation with project partners in Germany. In addition, all relevant data on policy measures at company level (e.g. participation in temporary decommissioning) and at national or EU level (e.g. quotas, nature conservation measures, other restrictions on fishing) will be collected from the relevant authorities and public sources and merged with landings data. In addition, suitable data sources with stock estimates (e.g. from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea - ICES) and data on vessel characteristics from the European Fleet Register are integrated.

Work package 3: Analyses

Dieter Kömle, Sean Pascoe, Yifan Lu, Gabriela Scheufele, Christoph Tribl

Once the data has been acquired and cleansed, the actual analysis begins. The analysis has three stages and combines unsupervised learning to reduce the complexity of the input data (grouping fish species into species groups using clustering), non-parametric efficiency analysis (Bogetoft and Otto 2010), and machine-learning-driven causal inference (supervised learning) (Bach et al. 2024; Chernozhukov et al. 2018). As a result, parameters are estimated that describe the influence of the respective policy measures on efficiency (focus on allocative efficiency). The results and methodological approaches are continuously discussed with the co-authors by means of feedback loops.

Work package 4: Publication and dissemination

Dieter Kömle, Robert Arlinghaus, Sean Pascoe, Yifan Lu, Gabriela Scheufele, Christoph Tribl

The knowledge gained regarding the suitability of the methods for further policy evaluations (e.g. similar measures of the CAP Strategic Plan) as well as the conclusions for policy measures and the course of the project will be summarised in work package 4 in the form of a final report.

A central component of work package 4 is the writing of a scientific article for the scientific community. A submission will be made to a suitable international peer-reviewed scientific journal (either a general interest journal such as PNAS, or a specialised journal such as Marine Policy). Through participation in international conferences and internal feedback rounds, the content and analysis will be iteratively revised and improved until it is ready for publication. After publication, the publication is presented to a broader public via suitable popular science formats. The methodological and content-related insights gained will be used to design follow-up projects.

Status of the project

The project is initiated for 2025.

Work in 2025

In 2025, the project is initiated with all project partners at the beginning of the year. This will be followed by the literature analysis (WP1) and data acquisition and cleansing (WP2). Initial analyses are planned for the end of 2025.

Timetable

Project start: 01/2025

Project end: 12/2026

Project partner

Prof. Dr. Robert Arlinghaus ist Forschungsgruppenleiter für integratives Fischereimanagement am IGB sowie Professor an der Humboldt Universität zu Berlin und forscht seit vielen Jahren in der Studienregion. Sein Fokus liegt auf der Verbindung von Natur- und Sozialwissenschaften im fischereilichen Kontext (Freizeit- und Erwerbsfischerei). Neben seinen wissenschaftlichen Publikationen ist er auch sehr aktiv in der Wissenschaftskommunikation tätig, was sich im Gewinn des prestigeträchtigen Communicator Awards der DFG in 2020 niederschlug. Im Projekt marEEchange untersucht er gemeinsam mit Dr. Yifan Lu derzeit Kipppunkte und Strukturwandel in der Dorschfischerei in der westlichen Ostsee.

Dr. Yifan Lu ist ein angewandter Ökonom mit Fokus auf die Identifikation kausaler Zusammenhänge zwischen Fischerei und menschlichem Verhalten unter Nutzung natürlicher Experimente (Difference-in-Difference, Regression Discontinuity Analysis). Er ist auf Mehrarten-Fischerei spezialisiert und hat Erfahrung mit der Ostsee (Dorsch und Hering), indonesischen Küstengewässern und der Antarktis.

Dr. Sean Pascoe ist Fischereiökonom an der Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) in Brisbane, Australien. Er bringt viel Expertise in Effizienzanalysen in der weltweiten kommerziellen Fischerei mit, war bereits an bisherigen Projekten beteiligt und ist Koautor für einen Artikel, der in der Fachzeitschrift „Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences“ akzeptiert wurde (Koemle u. a. 2024).

Dr. Gabriela Scheufele (CSIRO) ist Ressourcenökonomin und forscht ebenfalls seit vielen Jahren in der Fischerei. Dr. Scheufele bringt große Expertise in ökonometrischen Analysen im Umweltressourcen- und Fischereikontext mit.

Literatur

Arlinghaus, Robert, Marlon Braun, Felicie Dhellemmes, Elias Ehrlich, Fritz Feldhege, Dieter Koemle, Dominique Niessner, u. a. 2023. „Boddenhecht - Ökologie, Nutzung und Schutz von Hechten in den Küstengewässern Mecklenburg-Vorpommerns“. 33. Berichte des IGB. Berlin, Germany: Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries. https://doi.org/10.4126/FRL01-006453300.

Asche, Frank, und Kristin H. Roll. 2018. „Economic inefficiency in a revenue setting: the Norwegian whitefish fishery“. Applied Economics 50 (56): 6112–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1489502.

Bach, Philipp, Malte S. Kurz, Victor Chernozhukov, Martin Spindler, und Sven Klaassen. 2024. „DoubleML: An Object-Oriented Implementation of Double Machine Learning in R“. Journal of Statistical Software 108 (Februar):1–56. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v108.i03.

Bogetoft, Peter, und Lars Otto. 2010. Benchmarking with DEA, SFA, and R. Springer Science & Business Media.

Brümmer, Bernhard, und Jens-Peter Loy. 2000. „The Technical Efficiency Impact of Farm Credit Programmes: A Case Study of Northern Germany“. Journal of Agricultural Economics 51 (3): 405–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2000.tb01239.x.

Chernozhukov, Victor, Denis Chetverikov, Mert Demirer, Esther Duflo, Christian Hansen, Whitney Newey, und James Robins. 2018. „Double/debiased machine learning for treatment and structural parameters“. The Econometrics Journal 21 (1): C1–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/ectj.12097.

Coelli, Timothy J., Dodla Sai Prasada Rao, Christopher J. O’Donnell, und George Edward Battese. 2005. An Introduction to Efficiency and Productivity Analysis. Springer Science & Business Media.

Cunningham, Scott. 2021. Causal Inference: The Mixtape. Yale University Press.

Djokoto, Justice. 2015. „Technical Efficiency of Organic Agriculture: A Quantitative Review“. Studies in Agricultural Economics 117 (2): 61–71. https://doi.org/10.7896/j.1512.

Dresdner, Jorge, Nélyda Campos, und Carlos Chávez. 2010. „The Impact of Individual Quotas on Technical Efficiency: Does Quality Matter?“ Environment and Development Economics 15 (5): 585–607. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X10000215.

Estrada, Gloria Angélica Chávez, Miguel Ángel Quiroga Suazo, und Jorge David Dresdner Cid. 2017. „The Effect of Collective Rights-Based Management on Technical Efficiency: The Case of Chile’s Common Sardine and Anchovy Fishery“. Marine Resource Economics 33 (1): 87–112. https://doi.org/10.1086/696130.

Huber, Martin. 2023. Causal Analysis: Impact Evaluation and Causal Machine Learning with Applications in R. MIT Press.

Koemle, Dieter, Thang Dao Nguyen, Xiaohua Yu, und Robert Arlinghaus. 2023. „Subsidies, Temporary Laying-Up, and Efficiency in a Coastal Commercial Fishery“. Marine Resource Economics 38 (2): 153–79. https://doi.org/10.1086/723731.

Koemle, Dieter, Sean Pascoe, Marc Simon Weltersbach, Birgit Gassler, und Robert Arlinghaus. 2024. „How quota cuts, recreational fishing, and predator conservation can shape coastal commercial fishery efforts“. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, August. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2024-0081.

Kotte, Volker, und Andrea Stöckmann. 2024. „Strukturwandel in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern“. IAB-Regional Nord. https://doi.org/10.48720/IAB.REN.2402.

Kumbhakar, Subal C., und C. A. Knox Lovell. 2003. Stochastic Frontier Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Lado, Ernesto Penas. 2016. The Common Fisheries Policy: The Quest for Sustainability. John Wiley & Sons.

Latruffe, Laure, Boris E. Bravo-Ureta, Alain Carpentier, Yann Desjeux, und Víctor H. Moreira. 2017. „Subsidies and Technical Efficiency in Agriculture: Evidence from European Dairy Farms“. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 99 (3): 783–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaw077.

Lewin, Wolf-Christian, Fanny Barz, Marc Simon Weltersbach, und Harry V. Strehlow. 2023. „Trends in a European coastal fishery with a special focus on small-scale fishers – Implications for fisheries policies and management“. Marine Policy 155 (September):105680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105680.

Möllmann, Christian, Xochitl Cormon, Steffen Funk, Saskia A. Otto, Jörn O. Schmidt, Heike Schwermer, Camilla Sguotti, Rudi Voss, und Martin Quaas. 2021. „Tipping Point Realized in Cod Fishery“. Scientific Reports 11 (1): 14259. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93843-z.

Nowak, Anna, Tomasz Kijek, und Katarzyna Domańska. 2015. „Technical Efficiency and Its Determinants in the European Union“. Agricultural Economics (Zemědělská Ekonomika) 61 (6): 275–83. https://doi.org/10.17221/200/2014-AGRICECON.

Pascoe, Sean. 2007. „Estimation of cost functions in a data poor environment: the case of capacity estimation in fisheries“. Applied Economics 39 (20): 2643–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840600722257.

Pascoe, Sean, Parastoo Hassaszahed, Jesper Anderson, und Knud Korsbrekke. 2003. „Economic versus physical input measures in the analysis of technical efficiency in fisheries“. Applied Economics 35 (15): 1699–1710. https://doi.org/10.1080/0003684032000134574.

Pascoe, Sean, Phoebe Koundouri, und Trond Bjørndal. 2007. „Estimating Targeting Ability in Multi-Species Fisheries: A Primal Multi-Output Distance Function Approach“. Land Economics 83 (3): 382–97. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.83.3.382.

Pascoe, Sean, Stephanie McWhinnie, Eriko Hoshino, und Robert Curtotti. 2022. „Using Productivity Analysis in Fisheries Management“. Canberra, Australia: FDRC. https://www.frdc.com.au/sites/default/files/products/2019-026%20Guide%20to%20Using%20Productivity%20Analysis%20in%20Fisheries%20Management.pdf.

Pauly, Daniel, Villy Christensen, Sylvie Guénette, Tony J. Pitcher, U. Rashid Sumaila, Carl J. Walters, R. Watson, und Dirk Zeller. 2002. „Towards Sustainability in World Fisheries“. Nature 418 (6898): 689–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01017.

Pearl, Judea, Madelyn Glymour, und Nicholas P. Jewell. 2016. Causal Inference in Statistics: A Primer. John Wiley & Sons.

Pe’er, Guy, Aletta Bonn, Helge Bruelheide, Petra Dieker, Nico Eisenhauer, Peter H. Feindt, Gregor Hagedorn, u. a. 2020. „Action Needed for the EU Common Agricultural Policy to Address Sustainability Challenges“. People and Nature 2 (2): 305–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10080.

Pikitch, Ellen K. 2012. „The Risks of Overfishing“. Science 338 (6106): 474–75. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1229965.

Stern, Elliot. 2009. „Evaluation Policy in the European Union and Its Institutions“. New Directions for Evaluation 2009 (123): 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.306.

Sumaila, U. Rashid. 2013. „How to make progress in disciplining overfishing subsidies“. ICES Journal of Marine Science 70 (2): 251–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fss173.

Sumaila, U. Rashid, Christophe Bellmann, und Alice Tipping. 2016. „Fishing for the future: An overview of challenges and opportunities“. Marine Policy 69 (Juli):173–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.01.003.

Thiam, Abdourahmane, Boris E. Bravo-Ureta, und Teodoro E. Rivas. 2001. „Technical Efficiency in Developing Country Agriculture: A Meta-Analysis“. Agricultural Economics 25 (2–3): 235–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2001.tb00204.x.